This article first appeared in BoF and McKinsey & Company‘s The State of Fashion 2019 report.

LONDON, United Kingdom — India is increasingly a focal point for the fashion industry, reflecting a rapidly growing middle-class and increasingly powerful manufacturing sector. These, together with strong economic fundamentals and growing tech-savvy, make India too important for international brands to ignore.

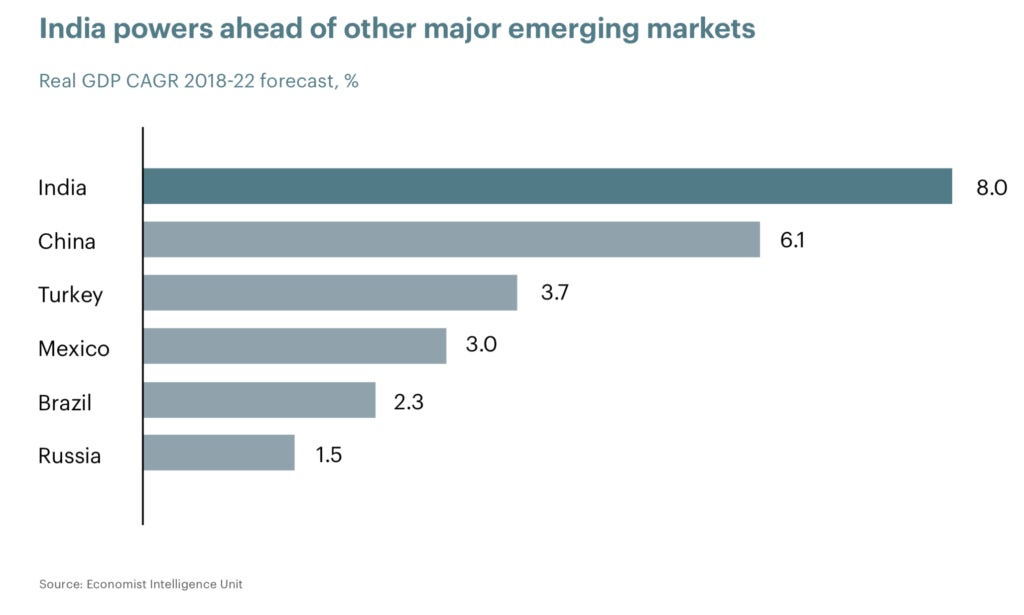

Economic expansion is happening across Asia, but we expect that 2019 will be the year in which India will take centre stage. The country is being propelled by strong macroeconomic tailwinds and is predicted to grow 8 percent a year between 2018 and 2022. The Indian middle class is forecast to expand at 19.4 percent a year over the same period, outpacing China, Mexico and Brazil. As a result, India is set to move from being an increasingly important sourcing hub to being one of the most attractive consumer markets outside the Western world.

India’s apparel market will be worth $59.3 billion in 2022, making it the sixth-largest in the world, and comparable to the UK ($65 billion) and Germany ($63.1 billion), according to data from McKinsey’s FashionScope. The aggregate income of the addressable population (individuals with over $9,500 in annual income) is expected to triple between now and 2025. According to Sanjay Kapoor, founder of Genesis Luxury, an Indian luxury retail conglomerate, higher incomes are likely to create a whole new class of consumer: “We are moving on towards the ‘gold collar’ worker. It’s a term that defines the well paid, highly paid professionals, who are happy to look good, happy to feel good and are expanding the consumption of today.”

India powers ahead of other major emerging markets | Source: Economist Intelligence Unit

Given these dynamics, it is little surprise that more than 300 international fashion brands are expected to open stores in India in the next two years. But India remains a complex market, which presents challenges as well as opportunities. The apparel business is still largely “unorganised,” with formal retail accounting for just 35 percent of sales in 2016. Its share is likely to reach around 45 percent by 2025, still a relatively low proportion.

To build momentum around conventional stores, Indian players are innovating the retail experience. Retailers are leveraging technology to enhance the in-store experience with digital marketing displays and improved check-out. For instance, Madura Fashion & Lifestyle launched the “Van Heusen Style Studio,” which uses augmented reality to display outfits on customers. Malls have increased their share of food service and entertainment.

The growth in the apparel sector is also being driven by increasing tech-savviness among consumers. Ten years ago, technology was for the few, with just five million smartphones in a country of 1.2 billion people and only 45 million using the Internet. These figures have since increased to 355 million and 460 million respectively (2018) and are expected to double by 2021, when more than 900 million Indian consumers will be online.

E-commerce leaders are moving to AI-based solutions. “Personalisation and curation, based on personal taste will become a lot more important,” says Ananth Narayanan, chief executive of Myntra, a fashion e-commerce player acquired by Flipkart in 2014. “It’s not about having the largest selection, it’s about presenting the most appropriate selection to the customer involved.”

The supply side of the industry is equally robust, and the growth of textile and apparel exports is expected to accelerate. According to a 2017 McKinsey survey, 41 percent of chief procurement officers expect to increase their sourcing share from India. India’s average labour cost is significantly lower than China’s and comparable with Vietnam’s. There is also a high availability of raw materials (e.g., cotton, wool, silk, and jute), which enable participation in the entire fashion value chain.

Still, players looking to enter the Indian market should recognise several inherent challenges. First, India is a mosaic of climates and tastes. “If you break [India] up into four parts, i.e., north, east, south and west, North India is the only region which is going to have winter, where you have mild to severe winter for eight weeks,” says Kapoor.

We are moving on towards the ‘gold collar’ worker.

“Brands that are successful in India have understood that, how [Indians] consume, what colour they consume, what kind of designs work, what touch points and personalisation work may be very different from a consumer living in New York or Hong Kong,” Kapoor adds. “Indian women have kept a lot of their traditional sensibilities alive and you see a beautiful mix of both Indian and

Western sensibilities across the spectrum.”

International companies considering an entry into India should heed this important message. Traditional clothing is still very much the default choice for women, making up an estimated 70 percent of women’s apparel sales in 2017. Appetite for Western styles is likely to increase, but it is expected that traditional wear will still account for a 65 percent market share by 2023.

Another challenge is the low quality of India’s infrastructure, which continues to lag behind that of many other Asian countries. Nearly 40 percent of the Indian road network was unpaved as of 2016. Poor infrastructure can make last-mile delivery difficult. In addition, retail stock is also often below expectations.

However, there are signs of improvement. “We have two fantastic luxury malls coming up in Bombay at the Bandra Kurla Complex along with the convention centre,” says Darshan Mehta, founder and chief executive of Reliance Brands, which operates over 500 stores for international brands. “So there is a whole new fantastic retail ecosystem.”

One sign of India’s challenges, and also an indication of latent demand, is the growing level of inequality in the country, which follows a broader global trend of rising income inequality. The gap between the top one percent of earners and the middle class is at its highest level in 92 years. Another consideration is the possibility of corruption. According to Transparency International, India ranks 81stout of 180 countries on its Corruption Perception Index (versus China at 77). A significant number of licences is required for new entrants, so executives should beware of the potential for complicated negotiations.

Indian women enter a store at the DLF Emporio luxury shopping centre in New Delhi | Photo: Brian Sokol via Getty Images

Still, many brands are determined to take advantage of India’s blossoming growth. The majority are likely to choose one of three routes. First, players can partner with existing e-commerce platforms. This is most suitable for players with little brand awareness and with relatively low capital to invest, and offers a good way to test demand and customer preferences. Second, brands that have little local knowledge and are looking for fast entry can enter with a franchise model, developing brick and mortar retail spaces. Finally, players that have significant local knowledge and capital resources can create fully owned and operated stores.

Indian authorities are certainly keen to promote investment. Relaxed FDI regulations (e.g., allowing 100 percent foreign-owned single brand retail operations), will likely lead to more overseas-originated activity through the value chain. We expect more outsourcing and more brand-owned stores without Indian partners in the years ahead. Most activity is likely to be focused on major urban centres, reflecting demographic trends, rising urban consumer spending power and improving infrastructure in those areas.

In short, the Indian market offers great promise. Despite structural challenges that include inequality, infrastructure and market fragmentation, we expect strong economic growth, scale and rising tech-savviness will combine to make it the next big global opportunity in fashion and apparel.